How to Catch a Gravity Wave

A Story About Human growth and the Power of the Scientific Method

"When the dinosaurs looked up to the sky, they saw...nothing. Because "not far" in this universe was still 130 million light years away."

"Civilization was born, and they called themselves human..."

Does Anyone Notice When Neutron Stars Collide

It's the Spinning Before the Crash that Makes the Waves

"If two neutron stars collide in a distant galaxy, and no one can detect it, does it make a gravity wave?"

That's not just a clever twist on an old philosophical thought, but a real physics question, first hypothesized (admitedly with a little less mysticism) by a scientist in the early 1900's. At least the existence of gravity waves was hypothesized — they didn't know about neutron stars yet.

(Credit: P. Hurt, Caltech, NASA-JPL)

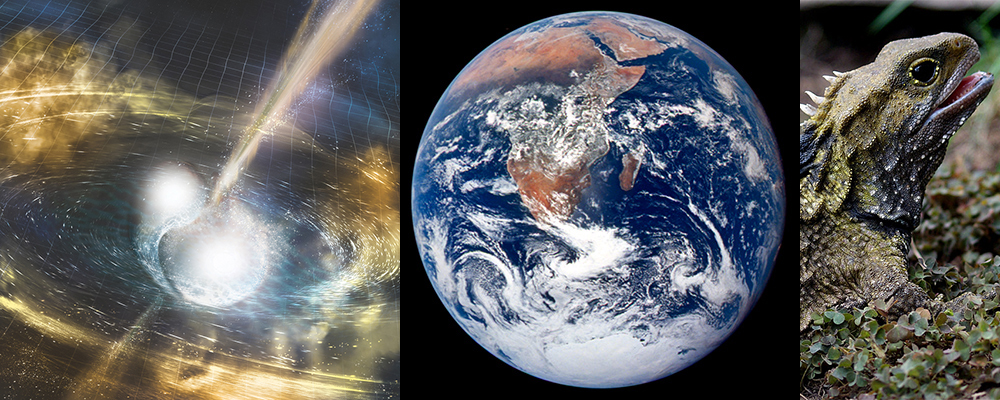

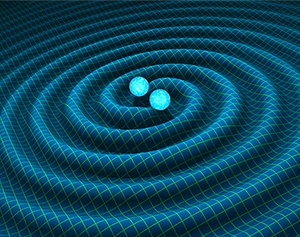

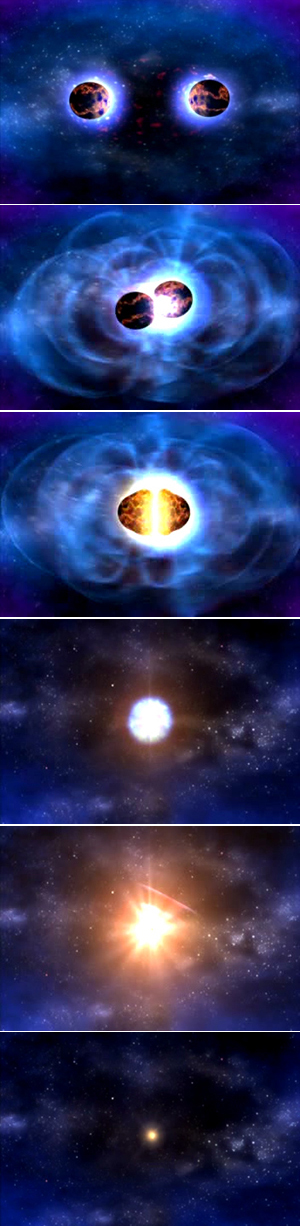

This particular true story started one hundred and thirty million years ago, give or take, in a typical galaxy, not so far away. Two neutron stars got too close. Though each star had a diameter of just 20 kilometers (12 miles) or so, their individual masses were from 1.1 to 1.6 times the mass of the sun. The stars whirled around each other at hundreds of revolutions per second, drawing closer and closer, unable to break apart because of the emmense gravity field pulling them together.

The frantic spinning of such massively dense and heavy objects created intense gravity waves that spiraled outward at the speed of light, literally disrupting space and time as they rippled out into the galaxy and then the universe.

Then the stars finally merged into a creative violence that resulted in, among other things, new elements and a very bright light — with an afterglow that stayed a while.

What the Dinosaurs Never Knew

Not far from the colliding neutron stars, as distances in this universe go, there was a smallish planet circling an ordinary sun in the outskirts of a plain medium galaxy. If looked at from its only moon, just a couple hundred thousand miles away, the little planet appeared as a bright blue and white marble. At the time of the merging, the planet was probably dominated, as it still is, by microbes, viruses, and possibly ants. But a size-prejudiced observer might have concluded that the large dinosaurs walking on its surface were in charge.

Those merging neutron stars gave off a hec of a bright light. When the dinosaurs looked up to the sky, they saw ... nothing. Because "not far" in this universe was still 130 million light years away. It would take 130 million years for the light and gravity waves from that event to reach their beautiful little blue and white world.

The dinosaurs were not concerned with the collision of two collapsed neutron stars and the resulting gravity waves. Nor should they have been. By the time those once frighteningly disruptive waves would reach earth, in the incomprehensibly distant future, the space-time distortion they would create would be imperceptibly small — thousands of times smaller than the nucleus of an atom. Nothing alive could possibly notice.

The probability of any life-forms on that planet ever knowing about, let alone comprehending, the massive cosmic events taking place at distances beyond imagination was too small to calculate. Like all the waves before them, these would surely pass unnoticed.

But life kept changing. There were massive extinctions. Life recovered and diversified again, and again, and then again. Eventually, in the very recent past of the blue planet's life span, a medium sized primate left the trees and began to walk on two legs. Much more time passed and the primate grew and changed. They became tailess apes walking persistently upright on their two hind legs. That left the other two legs free to become arms. And at the end of those two arms were now the most extraordinary and flexible hands. What to do with those?

Hands, Brains, and Imagination

How about turning them into tools that, coupled with a large complex brain capable of imagining and questioning and creating like no other known life-form, could be used to create other tools. And that's what they did. Through a combination of trial and error, serendipity, and imagination, they made more and more useful things. They learned to work together — well most of the time. They also fought a lot. But when they did work together, it was astonishing what they could accomplish.

Centuries passed. They kept making better and more productive tools, art and music for pleasure and growth, and, of course, weapons for hunting, self-protection, and doing unto others what they would not have done to themselves.

Those productive tools meant that one clever two-legged, two-handed ape, could now do the same work that had previously taken many to do. This allowed specialization and division of labor. Many clever apes were freed to spend most of their time on specialty tasks not tied to immediate survival. At first these specialists were priests, craftsmen, bosses, and administrators. Then there were lawyers, talk show hosts, realtors, and most important, at least for this article, scientists and engineers.

Civilization was born, and they called themselves human.

Next page: How to Catch a Gravity Wave - Part 2

Next page: Part 2: How to Get Out of a Thinking Rut

FT Exploring: Home Page